Larry Allen has worked in various jobs at Dallas Fort Worth international airport for over 40 years.

Before the pandemic, Allen worked as a baggage handler, making just over $2 an hour and relying on tips to get by. When Covid-19 hit the US, Allen was told not to come back into work and wasn’t recalled until one year later, when he took a position as a wheelchair agent.

He now makes only $8 an hour, plus tips, but those tips aren’t guaranteed and can vary widely and he relies on social security benefits and Medicare. In his late 60s, Allen walks a few miles every day at work, and at his age worries about the physical toll working in the airport has taken on his body and his ability to eventually retire comfortably.

He is pushing to organize a union among his co-workers at the airport to improve wages, benefits and working conditions.

“We need more money and more respect for the work we do. Eight dollars an hour is just not enough,” said Allen. “A union is an advantage, to get proper wage and insurance so if you get sick, you’ll have some medical coverage, and if something happens, you’ll have somebody to represent you and back you up.”

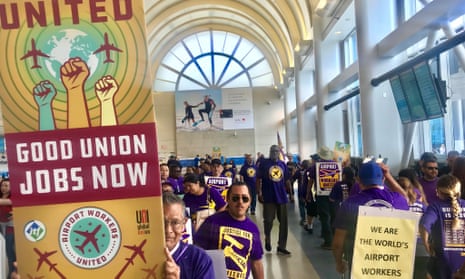

Allen is one of many airport workers around the US who took part in protest actions last month to pressure government officials at local, state and federal levels, and the CEOs of large airlines, including United, Delta and American Airlines, to sign on to a Good Airports pledge, committing to ensuring airport workers are paid living wages, provided affordable healthcare and have the right to organize a union.

The actions were part of a campaign led by the Service Employees International Union (SEIU) for airport workers to bargain through a union for improved pay, working conditions, healthcare and sick leave.

Contracted workers, including baggage handlers, cabin cleaners, security guards, wheelchair attendants and janitorial staff participated in actions at United Airlines and American Airlines headquarters and airports in Atlanta, Boston, Philadelphia, New York City, Miami, Houston, San Francisco, Los Angeles, Seattle, Minneapolis, Orlando, Tampa, Fort Lauderdale, Washington DC, Portland, Newark, Chicago. and Denver. New union organizing efforts were launched in Phoenix, Dallas and Charlotte.

“I’m only paid $12 an hour. I work a lot of hours and some days I work so late that I just sleep over at the airport. I can’t afford a car, rent and to send money home to my family in Sudan,” said Omer Hussein, a wheelchair attendant servicing American Airlines at Dallas Fort Worth international airport, in a press release on the actions. “I like working with passengers, but I’m so tired all the time. That won’t fly any longer.”

Airline contractors have reported difficulties in staffing positions as air travel demand has continued to improve toward pre-pandemic levels. Airline corporations have increasingly outsourced work to contractors in recent decades, which often pay workers low wages with few or no benefits.

The SEIU cited data on the demographics of contracted airport workers in the US, revealing that 64% are people of color and are paid 42% less on average than their white peers in the air transportation industry.

Mary Kay Henry, president of the SEIU, said workers were speaking up to hold airlines accountable because they are paid from the profits of these companies through contractors. She characterized the actions as part of a historic uprising of workers around the US demanding a voice on the job through a union and to be respected, protected and paid what they are worth.

“They’re speaking up to say they’re fed up with business as usual, because why should a worker in Chicago who drops a passenger off in a wheelchair get paid $18 an hour while the worker in Dallas who picks them up upon arrival gets paid only $8 an hour? Where your firm or the job you do are should not determine whether you support your family and can take care of yourself when you’re sick or have a voice on the job,” said Henry. “The major airlines can change the system of these jobs that used to be middle-class jobs with benefits that people could raise their families on.”